Discussions of the movie I, Robot tend to focus on how Asimovy it really was (or wasn’t). I was interested in another feature: how the uncanny valley was used in movie. This post talks a bit about what the uncanny valley is, how I, Robot used it and how that might relate to non-visual fiction.

Discussions of the movie I, Robot tend to focus on how Asimovy it really was (or wasn’t). I was interested in another feature: how the uncanny valley was used in movie. This post talks a bit about what the uncanny valley is, how I, Robot used it and how that might relate to non-visual fiction.

** includes spoilers for I, Robot **

What Is The Uncanny Valley?

The uncanny valley is a theory about how people react to increasingly human-like things. The theory states that people become more emotionally positive to things as they become increasingly human. A lizard is more like a human than a turnip, so lizards get more warm fuzzy feelings. A monkey is more like a human than a lizard, so monkeys get more warm fuzzy feelings.

But just before something reaches being a full human, there’s a drop in positive emotions towards it. This drop is the uncanny valley. It’s the point where a thing stops looking endearingly humanised and starts looking freakily sub-human. Or the point where a human is no longer seen as human and drops into the valley (zombies are the classic speculative fiction example of that… still all human and rather uncanny).

Robot design is an area where this matters. Makers want to make their robots human-like enough to make people feel good about them, but not step too far and fall into the valley.

Uncanny = Evil

The main use of the uncanny valley in the film is to signify evil.

The old robots are humanoid, but they have a blockier build and clearly robotic faces. They’re shown behaving in sympathetic ways, such as robots in storage huddling together. These robots are at the positive peak. They show sympathetic, human-like features, without appearing to be too human.

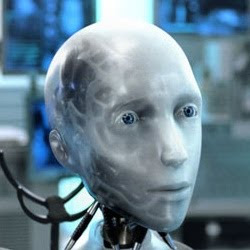

The new robots are down there in the valley. They have human-like faces, realistic eyes and rounded limbs, yet don’t look entirely human. Their voices are soft and more human-like than the old robots, yet also emotionless. The uncanny valley is telling you these robots are evil.

This is a pretty standard use of uncanny valleyness. It manipulates the audience into sympathising with the old robots and distrusting the new ones.

Why Don’t The Future People Think They’re Freaky?

Other than the protagonist, people trust the new robots. Even the protagonist doesn’t think they look untrustworthy (not any more so than the old robots anyway). So why don’t the future people think the robots are freaky?

One criticism of the uncanny valley is that it’s culturally based. A person’s experiences will change where (and possibly if) the valley exists. This is shown when humans drop into the valley.

Supposing you had a friend who didn’t have hands. You have no problem perceiving your friend as being human. A stranger isn’t used to your friend, and places him in the uncanny valley. The stranger’s reactions are hostile and untrusting. This example is unfortunately not that hypothetical – people with obvious deformities, scarring and missing limbs can end up in the uncanny valley and are treated accordingly.

The important point is that you and the stranger have different thresholds for what’s human and what’s not. However, given time, the stranger will get to know the friend, and will stop seeing hands as a defining human feature*.

Back to robots, it’s clear that a society’s view on robot appearance could modify. What’s uncanny at first may not be in a few generations time**. (On the other hand, it’s possible there’s a limit on what people would accept as human. As we have no evidence either way, a story could take either view***).

Why Do We Like Sonny?

Sonny is one of the uncanny robots. This is emphasised in his early appearances, by displaying almost human behaviour. He dreams and can draw, yet draws with precision with both hands at once. He’ll fight to survive, yet does so with superhuman strength and agility. Unlike our friend with no hands, he’s not displaying completely human behaviour. It’s going to be difficult to overcome that feeling of uncanniness.

By the end of the film, Sonny is showing human understanding of things like loyalty, deception and the value of free choice. It’s interesting that while watching the film, I have no trouble accepting Sonny, yet the screenshots still look creepy. Appearance may put a robot into the valley, but behaviour can pull them out of it.

This shouldn’t be a surprise, as behaviour is the thing that tells you real humans are humans. Often a screen robot looks uncanny because its behaviour is a little off (this can also be true of 3D animated people… the audience picks up on tiny errors in the movement that betrays the fact it’s a simulation).

How Do We Like Sonny?

This is a question that’s hard to answer. When we take someone or something back out of the valley, what are we actually doing? Do we see them as…

- A human (whether they are or not). Any differences are accepted as normal human variation.

- Near-human. We may not have had a category for that before, but our brains start to realise there’s a middle-ground between human and not.

- An exception. We’d still find others like them just as uncanny, but the individual is accepted.

In the case of the friend without hands, it’s going to be the first one. We soon realise that hands were never a defining part of being human anyway. The friend behaves in an entirely human way, so it’s not a difficult leap to make.

With Sonny, there’s still a voice saying he isn’t human. Whether we’re seeing him in a near-human category, or he’s just sneaking closer to be seen as fully human, is hard to say.

It would be fair to say that any one of those options could be realistic in a story.

Application to Fiction

Stories don’t have the same visuals as films, but the ways character might react may be based on this principle.

One interesting issue is that it might means it’s easier to accept a non-human robot as a sentient being with rights. The robot who falls in the valley has to overcome feelings of distrust – something an out-of-valley robot doesn’t have to contend with.

The robot Asimo is a classic out-of-valley design. Roughly humanoid and able to move in a human-like way, but robotic enough that he doesn’t fall in the valley. People react in a positive way to Asimo****, and this would obviously be a great advantage if Asimo were sentient and trying to gain rights. People wouldn’t assume he was evil.

On the other hand, Sonny has an uphill struggle. It’s interesting that the movie makers didn’t try to make Sonny look outwardly friendlier than the other new robots. The viewer has to overcome their own prejudices to see Sonny as anything other than the bad guy.

Few robot stories deal with the potential issues of a robot facing discrimination for its appearance. Perhaps a new robot line would be a little too human-looking and not sell as well, so they face being dismantled for parts. Perhaps when it comes to choosing between believing the blocky robot and the almost-human one, a character might go with their instinct and chose the blocky robot (possibly with disastrous consequences).

The sort of cultural change needed to accept an almost-human robot as human (or as definitely not human, and not uncanny) would take a long time to reach. In the meantime, all those robots in the valley have a problem. It’s odd that their problem doesn’t appear in fiction as much as you might expect.

–

* This has some real world significance too, because it suggests that it’s important for people to have experience of a wide range of people. If they don’t, they run they risk of seeing other humans as non-human.

** In Doctor Who, Donna (a modern day woman) meets automated greeters at a library in the future. These greeters have human faces on them, to put patrons at ease. They’re normal to the future people, but freaky to Donna.

*** Kryton, an android in Red Dwarf, has a blocky appearance. The crew discovers that earlier models look identical to humans. When asked why Kryton looks more primitive, he explains it’s because humans didn’t like their androids looking too human. Later models were made to look less human on purpose*****.

**** One example was the reaction to the Honda advert where Asimo moves through a museum. Some watchers were moved to tears, as it shows a very positive view of technology… a friendly robot reacting the way a human might to the museum exhibits. Few (if any) people thought “that robot looks like a mass murderer… I wouldn’t let him near those gadgets”.

The advert can be watched here. And just because it’s fun, dancing robots!

***** Though the way people react to humans in costumes is always somewhat different. Data from Star Trek was made to look slightly not human, in both behaviour and appearance. Yet he didn’t tend to set of people’s uncanny valley alarm. He’s a man in a costume and we know it.

–

Sonny photo is Copyright © Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation. Used for review purposes.

So glad you pointed this out.

I'd never heard of it but you're right — this happens.

Sometimes with cats too.

Hrrrr. Scary.

I love robots! Uh, not in THAT way … oh, never mind!

But I try to keep up on the latest advances and things, and I'm a member of the local hobby robot club. Two of my favorite sites are these:

http://robots.net

http://singularityhub.com

Here's that last site's articles on Hanson Robotics, which is doing a lot of work in this area. I keep wanting to tell the guy in the pic of that second article "She's nothing but a pretty face!"

http://singularityhub.com/tag/hanson-robotics/

I haven't seen the movie, but reality does seem to be different from your description of it – it's looking like robots will APPEAR fully human well before they learn to ACT fully human, so there may well be an Uncanny Valley equivalent in behavior or personality.

In fact, that idea has already shown up in fiction. There's a kitchen scene in the 1975 version of "The Stepford Wives" where a woman frustrated with the weird, "light" conversations with her "friend," shoves a knife into "her," who then repeats over and over, "Now THAT wasn't a nice thing to do … Now THAT wasn't a nice thing to do … Now THAT wasn't a nice thing to do …"

I've heard of the uncanny valley but I'd never thought of it in relation to writing fiction.