This is a small section of my art coursework, reviewing my visit to the Choucair exhibition at the Tate Modern. The overall coursework topic is “The Human Condition”, which is why the focus of the review is relating it to people. I figured it might be of interest to some of my blog readers.

Saloua Raouda Choucair (born 1916) is a Lebanese artist, known for her abstract art. I visited an exhibition at the Tate Modern, which covered her work throughout her career.

The first room displayed her earlier work, including pictures she’d produced whilst studying in France. Les Peintres Célèbres 1 has clear inspirations from Fernand Léger’s work (she studied at his studio), though the tone of the piece is different. Cubism and related styles are often violent to the subject, pulling them apart and reconstructing them. There is an overtone of hostility to the subjects. In contrast, Choucair’s women are organic and the scene is restful. That feel of domestic comfort acts as a critique of the work that inspired it.

Stepping away from her early work, her skill as an abstract artist is clear. Pieces such as Fractional Module show geometric shapes in bold colours, repeating and overlapping. There’s an influence from Islamic design, both in the patterns and the technique of starting with abstraction (rather than building up to it with figurative works first, as is commonly taught in Western art). Mathematical theory and poetry are common themes, giving the pieces a rhythmic tone. It’s a different approach to showing human experience than other artists I’ve looked at*, as she deals with the abstract aspects directly, rather than using the body as a focus.

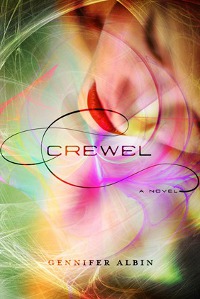

Her wooden sculptures particularly interested me. Some are towers made of multiple pieces, but it wasn’t clear at first glance whether this was the case or how many pieces had been used. By forming the wood into complex interlocking shapes, each tower forms a new combined shape.

The later sculptures move away from the colour of traditional Islamic art, with the use of wire, metal and other plain surfaces. The wire structures still have a repetition of line and curve, but it’s coupled with a focus on tension and energy.

The exhibition as a whole was well presented, with a good balance of sculptures, paintings and descriptions placing them in context. I find exhibits that are too heavy in one sort of work harder to get around, as all the work requires the same kind of attention. (This is something I’ll keep in mind when it comes to presentation of my own work.)

Choucair’s exhibit was popular enough to be extended for a few more weeks, which is very rare at the Tate Modern. Yet her work** has rarely been shown outside of the Middle East. It’s a reminder of how slanted art history has been, where the contributions of European artists are celebrated, whilst the work of others is often dismissed and forgotten. Hopefully this exhibition will help ensure Choucair is remembered.

–

* The ‘other artists I’ve looked at’ refers to the ones in my coursework, rather than all artists I’ve ever seen.

** Her page at the Tate’s website has the pieces they own: http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/saloua-raouda-choucair-14735

The Tate Modern has a section about the exhibition I visited, with photographs and details of the work: http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/saloua-raouda-choucair

# The picture is one of the wooden towers. It’s copyright to the Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation, and is used for the purposes of review.